On the evening of Monday 27th August 1877, the heavens opened along the Hillfoots. The rain was torrential and relentless.

In Tillicoultry the following morning, mill workers making their way for their 6 a.m. starts were absolutely drenched by the time they arrived.

Two hours later, thick black clouds formed and the resulting rain lashed down creating white foam over Tillicoultry Hill.

One eyewitness, Mr Benet, a former Dollar Academy teacher, said ‘the front of Tillicoultry Hill looked like a waterfall so gigantic as to dwarf Niagara ten times multiplied.’ He described it as ‘not simply heavy rain; it was a terrific downpour – persistent, incessant… a perfect sheet of water.’

The burn turned into a raging torrent at speeds never seen before. The first area it hit was the Burnside, then Mill Street and the High Street.

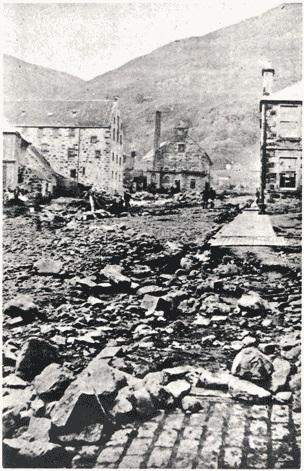

Roads disappeared and became rivers within minutes. Huge boulders dislodged from the hill hit the side of the burn’s walls.

This sound alerted the townsfolk to just how ferocious this catastrophe was. Mill workers found themselves trapped with the water rising steadily.

In the High Street, homes were destroyed and businesses water logged. People tried to barricade their front doors to no avail. The water continued towards the southern edge of the town, threatening to flood Paton’s Mill in Lower Mill Street. The workers however managed to put barricades and sandbags in place and this diverted the water away from the mill.

The fields became lochs with the River Devon bursting its banks, unable to cope with the volume of water gushing into it.

At around 8.30 that morning, at the Castle Mills near the entrance to the Glen, Mr William Hutchison, one of the mill owners, went out onto the wooden bridge which connected one part of the mill to another. The raging water passed beneath him.

He was joined by Andrew Marshall, a finisher, a young mill worker called Isabella Miller and a dryer, William Stillie.

Marshall warned Hutchison that the bridge was in danger of being washed away but the owner had replied that he had seen the burn that high once before.

Barely had Marshall said, ‘You may have done that, but you never heard so many stones coming down,’ when the bridge was swept away, and all with it, except Marshall who had been standing on the edge, only a few inches from them.

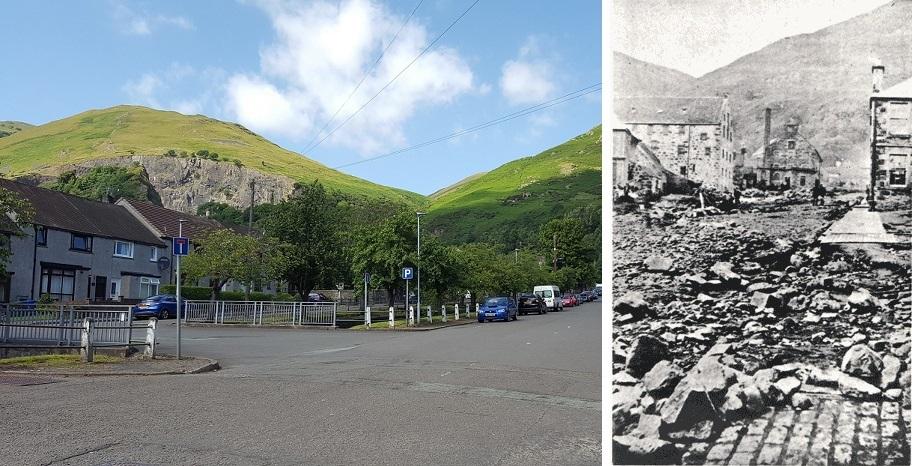

The Tillicoultry flood of August 1877 caused devastation with several people swept away in the raging burn.

William Stillie, a dryer, managed to grab hold of Isabella Miller, a mill worker, but the two were torn apart further down the burn when a rock struck and separated them.

He eventually seized a metal stanchion which was supporting a cellar windows of a house belonging to Mrs Alexander Robertson who lived next to Walkers Mill, further down the burn. Stillie was pulled to safety.

A search began for William Hutchison, a mill owner who was also swept away, and Isabella.

Meanwhile, workers in the power loom shed of Hutchison and Coy’s ran out to see what had happened. That proved to be a life-saving decision as the west end of the mill gave way and was carried down the burn, along with looms and shutes.

The roads on either side of the burn from the Heid o’ Toun Brig to the Middle o’ Toun Brig were washed away. It was thought the middle bridge was in danger of being washed away also; however, local men shored it up with barrels filled with stones.

At 2pm the body of William Hutchison was recovered near Oak Mill Bridge, having travelled around 1000 yards (915m). An extensive search took place for Isabella but her body was only found on September 1 at Glenfoot, where Tillicoultry Burn joins the River Devon.

The day following the flood most of the mills in the town re-opened, despite some workers spending much of the night clearing debris and watching as the weather deteriorated once more.

The rain poured down again, and people living on the Burnside prepared for more destruction. Men did what they could to shore up barricades

The Town Council opened the Popular Institute to receive furniture being salvaged from houses under threat. The rain finally receded at 6am.

On the day Isabella’s body was found, The Alloa Advertiser reported that the only word they could use to describe the destruction was ‘indescribable.’

The water had devastated the Burnside and High Street where boulders lay discarded, and what was left of the road was broken and almost impassable.

Such was the power behind the flow, the burn had managed to re-route itself, leaving mud feet deep, gas pipes exposed, streetlamps, walls and trees uprooted, and a new pavement destroyed.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here