CHRISTMAS EVE marked the 150th anniversary of the death of one of Tullibody's most famous sons.

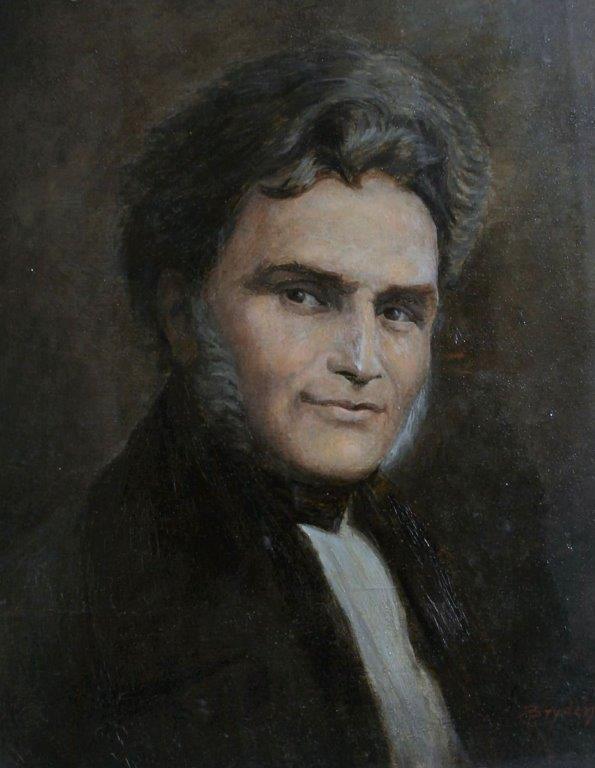

Robert Dick is renowned as one of the world's most influential geologists and botanists, despite being entirely self-taught.

However, he was also somewhat of a recluse who became uncomfortable with attention, to the extent of being considered anti-social.

Indeed, he passed on much of his work to others, with one eminent scientist once remarking: "He has robbed himself to do me service."

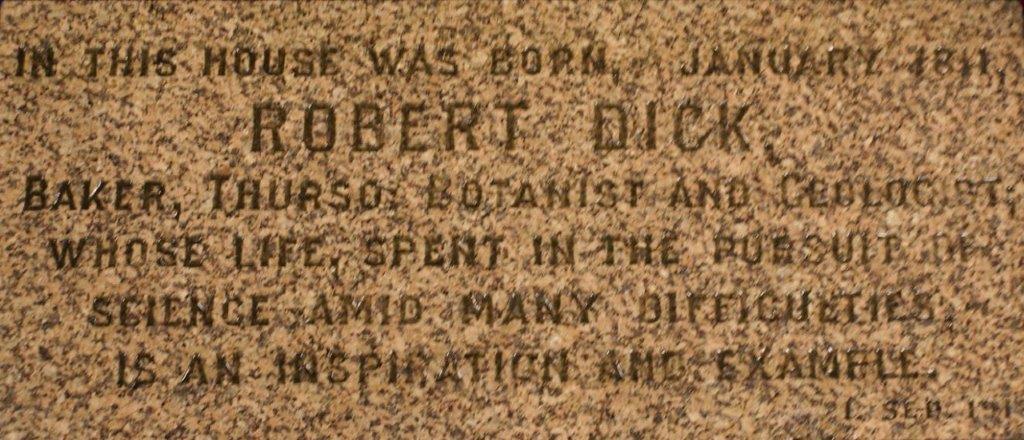

The son of an excise officer, Robert is believed to have been born in January 1811, the second of four children born to Thomas and Margaret Dick.

He attended the Tullibody Barony school which was partly maintained by the Abercromby family, before later moving to Menstrie after his mother's death.

The young Robert attended the subscription school there, but was to endure a fairly unhappy childhood with his new step-mother – said to have beaten his young brother "until he could not stand".

Later, as an adult, he would tell a fellow geologist: "...All my naturally youthful spirits were broken...to this day I feel the effects...it is this that makes me shrink from the world."

At 13, Robert became an apprentice baker with Mr Aikman at his shop where the post office is now located in Tullibody.

While making bread deliveries, sometimes as far as Blairlogie or even Bridge of Allan, the youngster would develop his interest in the natural history of the surrounding areas.

He later moved with his family to Thurso and opened a bakery; however, he spent his afternoons and evenings reading and wandering.

With a swelling interest in botany and geology, he began studying and collecting the plants, molluscs and insects of Caithness, eventually leading to the creation of his vast 'herbarium'.

He also discovered Holy Grass, which had not previously been found anywhere in Britain, on the banks of Thurso River.

Chris Calder, of the Tullibody History Group, said: "His botanical collection included some 4000 specimens, along with one sample from Tullibody.

"It was from the Tron Tree, which was planted in 1801 for Sir Ralph Abercromby's death. Robert asked his sister Agnes to send him a specimen and it is still in his collection in Thurso museum.

"The tree stood in Main Street near the present Health Centre and was chopped down in the 1950s when the village of Tullibody was redesigned.

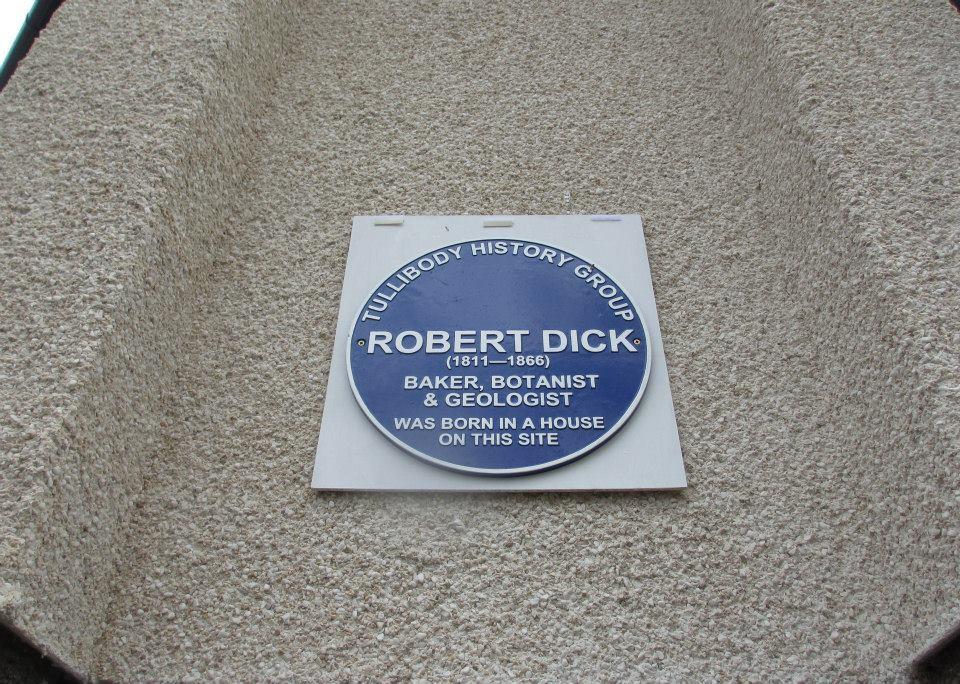

"The house he was born in, which is now Thanks a Bunch Florist, had been demolished by the council as well."

His reputation grew and he was later visited in his bakery by the era's most notable natural scientists, who praised such impressive work from a self-taught man.

Though he was described as becoming antisocial, having turned curious members of the public away.

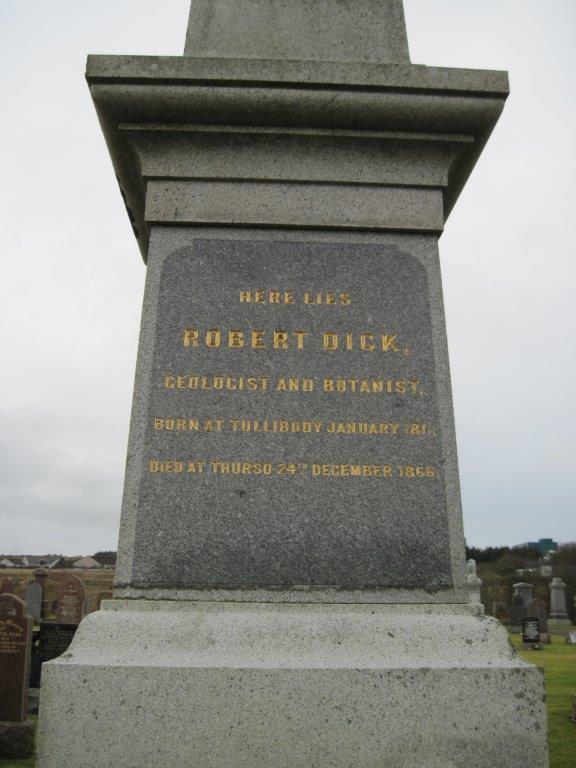

However in August 1866, he collapsed while collecting specimens in a quarry and never fully recovered. He later died on Christmas Eve that year.

Ms Calder added: "He was a bit of a hermit, and a pied piper. Everyone knows about Hugh Miller but not so many are aware of Robert Dick.

"But he was a highly intelligent guy and had he been born in today's times, he would have gone to university. That just wasn't available to him back then so he went off to make a living as a baker.

"Despite that he was actually one of the people that discovered exactly how the land in Scotland was laid down. At that time no one knew that volcanic eruptions had shaped the land, and he was able to prove that.

"His legacy also lives on as Dunnet Bay Distillery dedicated a bottle of vodka, laced with Holy Grass, to Robert.

"He also has an obelisk in Thurso cemetery as well as a plaque to him on Main Street in Tullibody."

Robert's work remains largely uncelebrated due to his deep aversion to publicity, but he is considered a major influence on the work of geologist Hugh Miller.

As director-general of the Geographical Society, Sir Roderick Murchison also spoke of Robert with great esteem.

He is reported to have said: "I found, to my great humiliation, that this baker knew infinitely more of botanical science, ay, ten times more, than I did and that there were only some twenty or thirty specimens of flowers (from the British flora) which he had not collected."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here