ON SUNDAY May 31, 1868, at around midday, a coal-pit on the estate belonging to Thomas Dundas, the Earl of Zetland, and leased by the Clackmannan Coal Company, was reported to be on fire.

A fire appliance was despatched from Carsebridge Distillery, and arrived quickly at the pit, and began tackling the blaze.

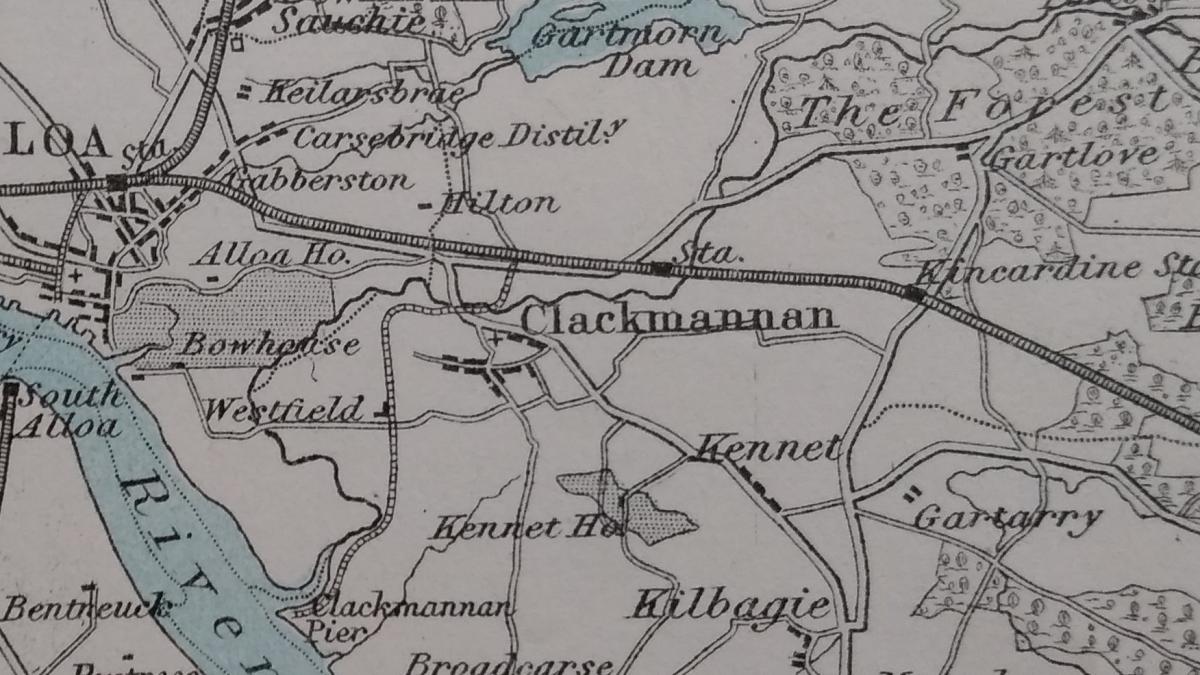

The fire began in what was known as No. 12 pit, situated near the eastern extremity of Gartmorn Dam, once used as the main water supply for Alloa, around two miles from the town itself.

The mine was about 130 feet deep, and had two seams, the lower one being splint, or banded, coal with the upper seam containing cherry coal. It was linked with another pit, No. 13, a short distance away.

Down through the centre of the shaft there was a mid-wall, constructed of wood, and the shaft on either side was lined with remnants.

About 30 feet from the bottom of the ventilating shaft there was a fire cube built of fire-brick, and in this cube, a fire was continuously kept alight for the purpose of securing the proper ventilation of the pit and for carrying off the foul air.

It was in connection with this fire cube that the May disaster was thought to have originated.

Late on the Saturday evening, the cube was believed to have been substantially overfilled with coal, and the heat rising from it was supposed to have ignited the foul coal only a few inches from the top of the cube.

This foul coal, once it caught, meant the flames would have risen higher and began to burn the ropes in the centre, the mid-wall of the shaft, and side-traces.

It was not, however, until about 11 o'clock on the Sunday morning that a neighbouring farmer, Mr. McLeish, of Gartmorn, saw the columns of black smoke rising from the pit, and raised the alarm.

By the time assistance was obtained, the pit-cradling on the top of the rock was not only completely destroyed, but the flames had reached the mouth of the pit, and had seized hold of the head-gearing, framework, shear-legs, and other machinery sited there.

By this time, no fire engine had arrived at the scene. The mound of coal on the hill was threatened by the rapid advance of the fire.

A crowd of workmen soon gathered, and an attempt was made to ascertain the extent of the blaze by approaching the bottom of the shaft through the communication leaning from pit No. 13.

FIRES, such as that at the Clackmannan pit, were not an unusual occurrence in mines.

Pit fires were a constant threat to life, as was flooding, but while this one raged, the miners became seriously concerned they would not be able to control it.

The density of the smoke running along the passages made it impossible to tackle as the thick smoke engulfed anyone who tried to make inroads in putting it out, so the men were forced to retreat and wait for the arrival of the fire engine from nearby Carsebridge.

On the arrival of the engine, the water was pumped directly onto the machinery, the framework and other gearing at the pit head, but the inferno had already been so intense that very little could be saved.

Part of the wreckage fell down the pit shaft, and it was found that pouring down water from the fire hose was doing little to extinguish the blaze while a continuous current of air was able to feed it.

The idea of flooding the mine was discussed but this was not carried out. It was finally agreed to try and attempt to extinguish the fire by smothering it.

With a view to trying this, the flow of air passing along from pit No. 13 was successfully checked by covering the pit-mouth with boards and fireclay.

Blac, or shale, and other refuse were thrown down the shaft over a considerable amount of time, then the pit-mouth of No. 12 was boarded up and was finally sealed by covering it with fireclay and piles of turf.

Nonetheless, smoke continued to rise, but the miners and firemen believed that the fire had been checked, and shortly after all these measures were in place, it was finally smothered.

The damage was costly, not only in terms of money but also jobs.

About 100 miners were made redundant due to the fire, with both pits having to be abandoned for a time.

From noon until around seven o'clock on the Sunday evening, when the pit heads were battened down, a continuous stream of people visited the scene as it was such an unusual occurrence in the area.

Although the disaster was one which many people were affected by, there was a feeling of relief that it was discovered during the day rather than at night which would have made the work much more difficult.

There was also the added benefit that there was no injury to any of the miners or firefighters, and no loss of life.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here